World Communications Day 2020 is celebrated on 24 May. This reflection, by Monsignor Peter Fleetwood, was written to provide homily notes for priests but equally can be read as a thought-provoking reflection on the theme before or after the day itself.

“That you may tell your children and grandchildren” (Exodus 10: 2)

World Communications Day 2020 is celebrated on 24 May. This reflection, by Monsignor Peter Fleetwood, was written to provide homily notes for priests but equally can be read as a thought-provoking reflection on the theme before or after the day itself.

One of the funniest things I have seen is a sign about half way along the road down from Jerusalem to Jericho. It points to “The Good Samaritan Inn”. Many a pilgrim will have seen the sign, and it echoes tales from many pilgrimage routes around the world, including the road taken by the pilgrims Geoffrey Chaucer brought to life in The Canterbury Tales – these tales often involve drinking and eating, and other things that happen in inns and hostels. The funny thing about the sign on the road to Jericho is that it has tricked thousands of pilgrims over the centuries who, presumably, have been thrilled to visit the place the Good Samaritan took the wounded traveller who had been mugged by highwaymen. It has tricked them because there was no inn. There was no wounded traveller. There was no Good Samaritan. It was all a story made up by Jesus, who must have been a great storyteller, because several of His stories have shaped the thoughts and beliefs of countless people who have read them in the Gospels, or heard them read out in churches Sunday after Sunday, year after year.

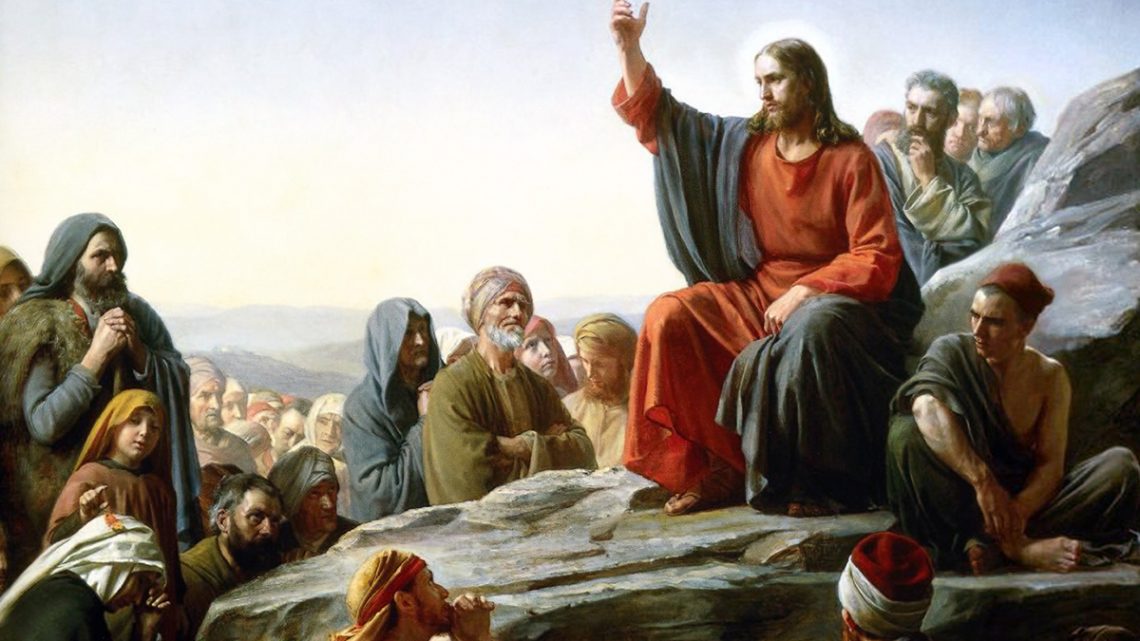

Jesus was not relating actual events in those stories. They were all things that could happen and those sorts of things did happen; people knew what He meant because He tapped into local news, into the way they lived, and He knew what amused them or made them angry or sad. The characters He described were like those His listeners knew or knew about. They recognised the heroes and the villains in the parables, and that enabled Jesus to make His point. His stories told of the Father’s astounding mercy, of our all-too familiar limitations and our feeble efforts to impress God and each other, of the danger of concentrating on the minutiae of religious rules and regulations and missing the point of them. Oh, yes, He made sure we knew He wasn’t about to abolish those rules and regulations, but He never missed an opportunity to tell a story that showed how small-minded we can be, and how big-hearted we need to be. The point is not only what He said, but the way He said it.

An exercise I have asked people to try is to imagine the expression on His face when He told these stories, or the tone of voice He used. Think about it. Does a good storyteller always speak in the same monotone, or does his or her voice ‘bounce around’, possibly throwing in a local accent or a bit of mimicry? Think of people whose attempts at telling jokes don’t work, and then think of the ones who have you spellbound, waiting desperately for the punch line. Guess which kind Jesus was. And now for the challenge. If Jesus was such a good storyteller, how should we speak when we read His stories or any of His words? How should we tell children about Him? How should we speak of Him in our homilies? How should we listen to Him? Many of the people who listen to our homilies were taught the words of the parables with a permanently earnest expressionless tone. Could we be the ones to help those people hear Jesus in a completely different way? We are all capable of sterilising the message, but are we equally capable of bringing it to life? An enclosed nun asked Mother Prioress if she could speak to me one day. She said in all her years as a Catholic she had found it difficult to see what relevance the Scriptures had. “But, Father, since you’ve been our chaplain, it’s been like discovering a box of treasure that you open for us every day and show us yet another precious jewel. I can’t wait for the homily at Mass now”. That came as a total surprise to me, but it shows what can happen if we allow the Word to take hold of us. The power in the words we handle every time we proclaim the Word of God is astounding.

One of the most endearing aspects of the Jewish religion is the Passover tradition of children asking the older people present at the Seder meal to tell them why they are gathered for this special meal. The reply is the story of the Exodus, the foundational story of the Chosen People. This ritual is designed to inculcate in younger generations a vivid awareness of what their Jewishness is about. The Exodus story tells them who they are as Jews. This is a simple but powerful device for strengthening awareness of identity. Just think what that might mean if we were to transfer this idea into Christian life. Generally a child asking in church “why are we here?” is actually making a statement, which could be translated as “I’m bored and I want to go home”. But what if a child really wanted to know why we gather, and what it’s all about. How can the older generations pass on their respect and love for their faith to younger generations? Is there any way our families could learn from this exchange between young and old in the Seder meal? Could we – should we – have a ritual re-telling of our story as Christians? In theory, we have the Liturgy of the Word, then someone breaks open the Word, but nobody has asked to hear those readings. Perhaps it cannot be done well in church, but would make more sense at home, or even in school. A homily on World Communications Day this year could hinge on suggesting to parents that it is possible to prompt children to ask, at a family meal or prayer time, what it is that makes us Christian? What is our story? This could also be a ‘thought for the week’ in a parish newsletter or on a parish website, or even the theme of a day of recollection for teachers or mothers (or fathers). The God who Speaks is a major focus of this year in the Church in England and Wales, and the power of the foundational story of our faith surely slots well into this. In parishes and communities which have taken it on board it would not be difficult to suggest embedding the value of re-telling our story in families, especially between the generations. Some of the new movements in the Church may have a lot to give in this area; I am thinking particularly of the Neo-Catechumenal Way, where children are brought up with the liturgy of the Word in a way I have seen nowhere else. It may not be right for everyone, but there is much to learn from a movement whose whole life revolves around the Word, and where children are familiar with it right from the start.